The KLF and how to write a hit song (or paper)

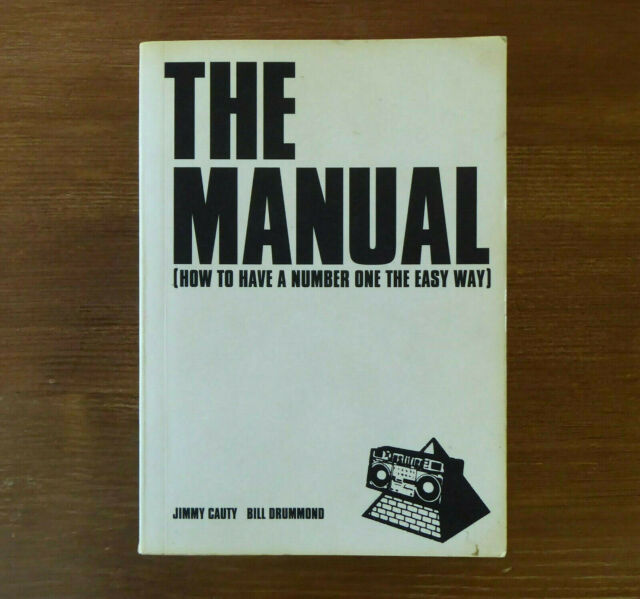

At ACL 2021, I led a mentoring group of early-stage PhD students, and I started talking about the KLF and the Manual, a book on how to write a song that would be guaranteed to get to no. 1 in the UK singles chart. The book was based on their personal experience taking a song based on the Doctor Who theme to no. 1. While originally meant as a joke, this blueprint was successfully used by another band to take a yodelling song to no. 1. In this blog post, I want to talk a little bit about the KLF, and why I think their philosophy is particularly relevant to researchers.

Who were the KLF, and why should you care?

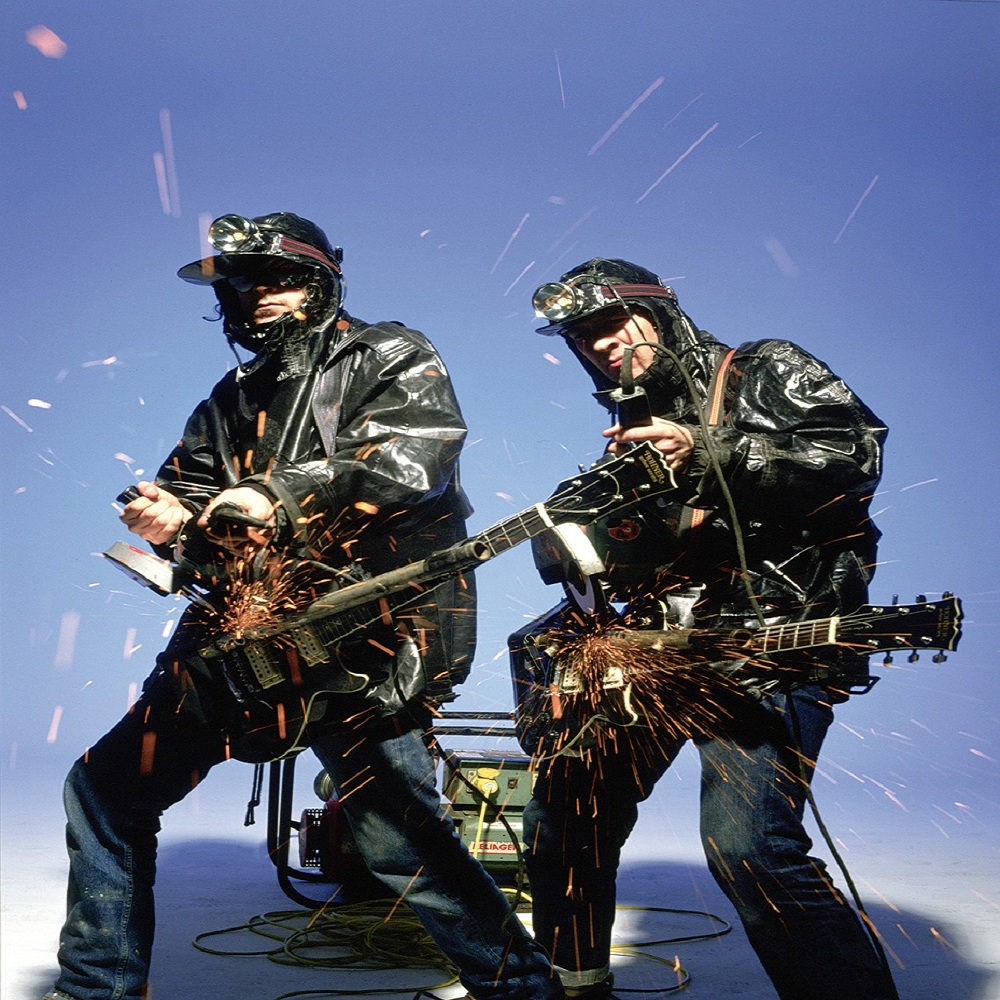

The KLF were an electronic music band, the biggest selling singles band in the world in 1991. They were the first to realise that not having to play instruments actually frees you up quite a lot, and created the idea of electronic music as spectacle in the Stadium House trilogy.1 They also managed to make country and western legend Tammy Wynette sing about driving an ice cream van, and segued a spoken list of northern British towns set to grinding industrial techno into the hymn Jerusalem (and took it to the top ten in the UK singles chart).

The two members of the KLF, Bill Drummond and Jimmy Cauty, had already been long-term members of the music business, both as musicians and managers of musicians, and so had a fairly good idea of how to make successful records by the time they started working together. They distilled their knowledge into their first no. 1 together, Doctorin’ the Tardis, mentioned in the intro as being based on the Doctor Who theme.

The Manual

However, unlike many no. 1 acts, the KLF then wrote a book detailing exactly the instructions that you, the reader with no musical talent, can follow to copy them and also get a no. 1 song. The book (full text linked in the section header) is chock full of glib insights into the music industry, such as the Eurocentric nature of music copyright, the emptiness of success, and the necessity in believing the benevolence of one’s fellow man.

However, the most important part of the Manual to us in the research game are the Golden Rules. These are fairly music-specific, but they all boil down to one message: you need to make your song as catchy as possible. For pop music, this involves having a killer groove that runs for the entire song, an annoyingly irresistble chorus, and a solid verse-chorus-verse structure. I recommend finding an hour or so in your life to read the Manual in full, especially if you’re interested in music and popular culture.

Why research is like popular music

(before I begin I would very much like to emphasise that these are my personal views about research, and do not represent any person or institution I may have ever or will be associated with)

I think research is a lot like popular music. Fundamentally, both arenas are battlegrounds of ideas, and your success largely depends on whether or not your ideas get noticed by the community at large or not. From this perspective, there’s a lot of good paper writing advice in the Manual. The core precept is to make your paper as ‘hooky’ as possible – every part of your paper, from the title, to the abstract, to the figures and tables, should be designed to be as informative and memorable as you can.

This is especially true for the bits of your paper actually read. As a rule of thumb, 90% of people who notice your paper will just read the title, 9% will read the abstract, and the remaining 1% will actually read the rest of the paper. This means that your paper title and abstract need to catch the attention of your target audience as much as possible. I personally am a big fan of abstracts which state the main contribution of the paper right in the first sentence, and titles which tell you exactly what the paper is about.2 This is advice the KLF also follow: the introductions of their songs are all very distinctive and memorable, and leave you wanting to hear the rest of the song.

The Manual’s advice about paper structure also transfers. By and large, you want to keep to the introduction/methods/experiment/results/conclusion framework as much as possible, as it offers readers a comforting blanket of familiarity when reading your paper. You’re allowed one wildcard section to highlight what’s distinctive about your research, analogous to the breakdown section recommended in the Manual. Until you’ve developed a certain amount of writing mastery, it’s not worth experimenting too much with form.

Finally, I’d like to talk about signposting – that is, letting the reader know what’s coming up next in your paper. This is something the KLF also advocate: if you listen to to the rapper in Justified and Ancient (the Tammy Wynette song), you can hear him introducing what musical elements are coming up next (‘to the top to the top’, ‘to the bridge’, ‘bring the beat back’). If it’s good enough for the KLF, it’s good enough for you and me.

What does ‘catchy’ mean?

(thanks to Guy Emerson for discussions which led to this section)

I’ve talked a lot about ‘catchiness’ in this post, but I haven’t really offered a definition of what makes a song (or paper) catchy. In part, this is because it’s hard to pin down: simple doesn’t necessarily mean catchy, although it’s a part of it. Neither does it mean you should dumb down your research in an effort to reach as many people as possible.

The best description I can give is that a paper is catchy if someone reading it immediately slaps their head and thinks ‘why didn’t I think of that’. For example, playground rhymes are catchy, and so is masked language modelling. The goal of your paper is to deliver your idea like a virus inside the reader’s brain and help it take up permanent lodging. I think it’s therefore helpful to consider the payload (the research idea) and the delivery mechanism (the actual paper writing itself) separately.

Having a good research idea is something that largely comes from experience in the field. It helps to read a lot of papers, so you can spot if there are any obvious holes in the existing literature that you can fill. A good way to generate a new idea is to combine two zeitgeist-y ideas into one (in my first paper I put an RNN inside word2vec, which is possibly the most 2016 thing you can think of). As you develop your own research taste, you’ll get more and more ideas, and then the difficulty becomes separating between good and bad ideas. This is where it helps to have friends to test ideas on: mention your ideas early and often to them, and see how they react.

However, it’s no use just having good ideas, you have to communicate them to other people as well, otherwise the idea will just wither and die. In NLP, the perferred delivery mechanism is the 8 page double-column conference paper, and I’ve already given some paper writing tips above. Sometimes, the idea is so good you don’t really need to dress it up too much for it to be transmitted; most of the time, you need to make the reader interested in your paper at least a little bit. What problem are you trying to solve? What new technique are you introducing, and is it more widely applicable? A little bit of motivation goes a long way, and eases the path of your research idea along the optic nerve from the eyes to the brain of the reader.

You too can write a hit paper!

For me, the most important message from the Manual is that there’s nothing stopping you from writing a hit song. The Manual updates the punk DIY attitude from playing in front of your mates in a garage to playing your song on the radio to potentially millions of listeners.

Similarly, the barriers to entry in NLP have been increasingly lowered in the past few years. Tools like HuggingFace let you download and run the latest machine learning models without having to implement and train them yourself. Google Colab even lets you run models on hardware accelerators, which means you don’t even necessarily need access to your own cluster. Virtual conferences let independent researchers join the community much more easily than before.

I would argue that now, NLP has reached the point where new researchers can start doing real research on topics of interest much more easily than before, which means that it’s never been easier to have an idea, write a paper and disseminate your research. And there’s nothing stopping you! Go out there and write!

Postscript: what happened to the KLF?

Nowadays, the KLF are perhaps best known for the manner in which they disbanded. The KLF were mostly interested in spectacle, rather than success, and disliked the actual reality of fame and fortune. They staged one final stunt as a band, playing a comedically aggressive version of 3 A.M. Eternal (the only member of the Stadium House trilogy to get to no. 1) at the 1993 Brit awards ceremony with extreme metal band Extreme Noise Terror, a performance which culminated with Bill Drummond firing blanks out of a live machine gun at the audience.

In an effort to get rid of the money they’d accrued, they set up an art foundation and donated £40,000 to fund a prize for the worst artist of the year (who coincidentally happened to be the Turner Prize winner that year as well). They also tried to symbolically display the money (in the form of £1,000,000 in banknotes) as a piece of art itself. Finally, in an effort to rid themselves of the money once and for all, they burned a million pounds on the island of Jura, recording it on video as their last artistic statement.